Pulling at a loose thread

One day I noticed an inconsistency as I was joining together lists of words. Consider this no-delimiter join:

arr = [ ['some', 'lists'], ['of', 'different', 'words'] ]

arr.map(&:join) # => ['somelists', 'ofdifferentwords']It’s point-free and clean, aside from the funny ampersand.

But look what happens if we hypenate instead:

arr = [ ['some', 'lists'], ['of', 'different', 'words'] ]

arr.map { |x| x.join('-') } # => ['some-lists', 'of-different-words']One more time, side by side:

The argument transforms the syntax entirely. What was pristine and simple becomes noisy and complex.

Why can’t we write:

I assumed for a long time this was a limitation of ruby, but then I got curious about that &, which I only half understood.

Turns out the & is needed any time a literal block is expected and you pass an object that responds to to_proc instead.

Despite appearances, then, both versions of map with join take a block and zero arguments. In the map(&:join) version, to_proc is called on the symbol :join, and the result is passed to map. Symbol defines to_proc in the way you’d expect:

and hence map(&:join) becomes:

So the map method never takes any arguments. How can we use this knowledge to achieve our coveted syntax: map(:join, '-')?

Refining the loose thread

Refinements let you safely alter core ruby library methods. They’re the well-behaved cousin of the monkey-patch – because they’re lexically scoped, they touch only code that’s using them.

With refinements, we can support the arr.map(:join, '-') syntax we want, do it exclusively in code that enables the feature, maintain full backward compatibility with the default syntax, and make the & optional.

These features, and everything else discussed in this post, are available in the pretty_ruby gem:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [ [1, 2, 3], ['a', 'b', 'c'] ]

arr.map(:join) # => ['123', 'abc']

arr.map(:join, '-') # => ['1-2-3', 'a-b-c']

# similarly...

[5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10].map(:%, 5) # => [0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 0]Continuing to tug…

We’ve stumbled upon a new way to represent Procs, but what if we need to chain them together? For example, say we need to increment and uppercase every letter in a list, and then join them with hyphens:

Once again, the brackets and our variable x are syntactic boilerplate. Taking inspiration from the Unix pipe | and Elixir’s pipe operator |>, we can refine ruby’s unused >> method on the Array and Symbol classes and write:

Or say we have an array containing arrays of numbers. We want the maxiumum “width” (number of digits) of each list. Our point-free syntax reduces noise and clarifies intent:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [ [1, 2, 3], [1, 32, 98], [56, 323, 1009] ]

# vanilla ruby...

arr.map {|x| x.map {|y| y.to_s.size}.max } #=> [1, 2, 4]

# pretty ruby...

arr.map([:map, :to_s >> :size] >> :max) #=> [1, 2, 4]Spotting other loose threads

Arrays possess a visual left-right symmetry which ruby exploits in its integer indexing:

as well as its Range indexing:

and rotate method:

Fixing take and drop

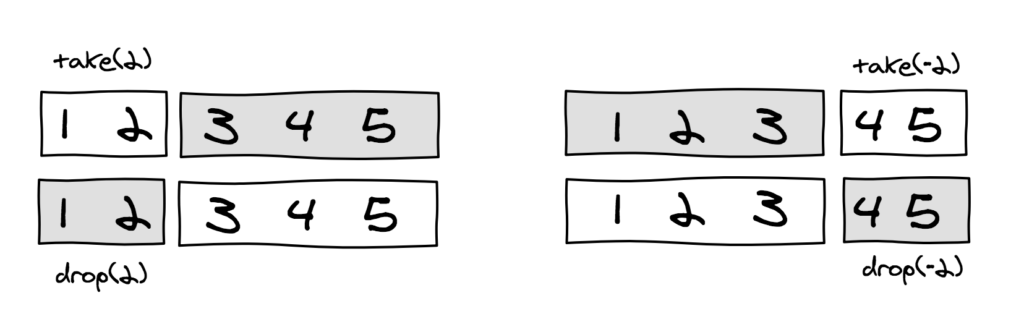

Yet negative versions are strangely absent from take and drop:

arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

arr.take(2) #=> [1, 2]

arr.take(-2) #=> ArgumentError: attempt to take negative size

arr.drop(2) #=> [3, 4, 5]

arr.drop(-2) #=> ArgumentError: attempt to take negative sizeVisualizing the four cases, we can see the missing mirror symmetries:

The negative versions of take and drop, moreover, are useful nearly as often as their positive counterparts.

Of course, Range indexing can solve the problem of taking and dropping from an array’s right side:

arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

p arr[-2..-1] #=> equivalent to take(-2)

p arr[0...-2] #=> equivalent to drop(-2)But notice how finnicky this is – two dots and two negative indexes for take, three dots and one negative index for drop – and observe how “dropping” is implemented by “taking the complement”. The solution doesn’t express its intent.

And then there is the larger dissonance between the ad-hoc negative solutions and the clearly named take and drop methods.

Let’s fix both problems and complete our set of four symmetric methods:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

arr.take(2) #=> [1, 2]

arr.take(-2) #=> [4, 5]

arr.drop(2) #=> [3, 4, 5]

arr.drop(-2) #=> [1, 2, 3]Completing first and last

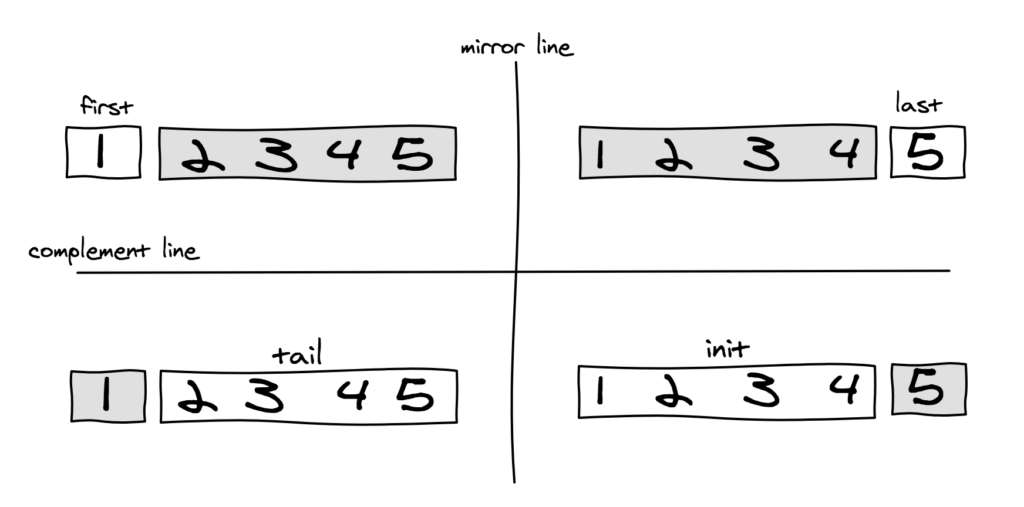

Built into Array are shortcuts for the special cases take(1) and take(-1), more commonly known as first and last. While rails offers cute shortcuts for second, third, fourth, and fifth, neither it nor ruby provide the more substantial ones for drop(1) and drop(-1), familiar to functional programmers as tail and init.

first/last and tail/init make mirror images, and the pairs themselves make “complement images” of each other. Reflecting about these two different symmetry lines, you can start with any one of the methods and generate the other three:

Let’s add these symmetries as well:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].tail #=> [2, 3, 4, 5]

[1, 2, 3, 4, 5].init #=> [1, 2, 3, 4]Weaving in new threads

Scan and avoiding reduce

How would you list the prefixes of the string “abcde”? Ordinary ruby requires something like:

'abcde'.chars.reduce(['']) { |m, x| m << m.last + x }.drop(1)

#=> ["a", "ab", "abc", "abcd", "abcde"]A somewhat labored solution. Generally, I think of reduce as a procedural wolf in functional clothing. The above is syntactic veneer over a loop:

Better to consider reduce as a low-level building block for higher-level constructs – more appropriate for library code than application code.

The construct we want here is the functional “scan”. (Imagine a finger “scanning” back and forth to produce the partial sequences)

Without any arguments, scan returns those partial sequences:

But once named and familiar, the concept comes up everywhere, Baader-Meinhof-like.

The partial sums of a sequence are the sum scan, and factorials are the multiplicative scan:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

arr.scan(:+) #=> [1, 3, 6, 10, 15]

arr.scan(:*) #=> [1, 2, 6, 24, 120]Say you’re recording temperatures every day, and want a running tally of the highest and lowest recordings so far. These are the “max scan” and “min scan”:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [81, 84, 80, 83, 87, 85, 77, 90, 91, 88]

arr.scan(:max) #=> [81, 84, 84, 84, 87, 87, 87, 90, 91, 91]

arr.scan(:min) #=> [81, 81, 80, 80, 80, 80, 77, 77, 77, 77]

# NB: we had to refine Numeric as well to make the above workNoting that rscan offers the same feature from the right side, we can (if we don’t mind O(n^2) complexity) solve the maximum subarray problem in one line:

require 'pretty_ruby'

using PrettyRuby

arr = [-2, 1, -3, 4, -1, 2, 1, -5, 4]

arr.scan.map(:rscan).flatten(1).max_by(:reduce, :+) #=> [1, 2, -1, 4]Tying the threads together

While cleaner syntax and declarative code are always valuable, and hacking ruby is plain fun, I think there’s more to refinements like these.

They change your mindset. They shift your perspective from passive consumer to creator. You see the language as something living, shaped by forces and choices and even mistakes, rather than something handed down from on high.

Most of all, changing the language forces you to understand it more deeply.

If you like these changes, you can install the pretty_ruby gem and start using them yourself.

Staff Writer

CyberArk uses a collection of staff writers and practitioners to support the DevOps Security.